The Waldauf foundation at St. Nicholas' church, Hall in Tirol

The founder, Florian Waldauf

Florian Waldauf (originally Baldauf) was born at Anras in the Pustertal, probably in the 1440s. Several colourful legends have become attached to his name, but most are either improbable or impossible to verify given the documentary evidence. In any case, the agricultural character of his family as presented in the older literature is an exaggeration; the high-quality stone monument to his father († 1493) on the outer wall of the church in Asch indicates that both of his parents had the right to bear heraldic arms. Waldauf’s literacy in German and Latin suggests that he attended a Latin school, probably at Innichen or Brixen. Despite the later legend that he studied at the University of Vienna, he does not appear in the matriculation lists there. On the other hand, there is good reason to suppose that he saw some military service.

Waldauf’s successful rise to prominence at court was aided by family connections. His uncle Hans Wieser von Rheinfelden, secretary to Archduke Sigmund of the Tyrol, significantly advanced Florian’s career. Another relative through marriage, Blasius Hölzl, an important official at the court at Innsbruck, may likewise have promoted him at court. Similar examples of social advancement through kinship networks are well attested at this time. An improvement of Waldauf’s heraldic arms (Wappenbesserung) in 1483 suggests that Sigmund appreciated his capable service.[1] However, he crossed soon afterwards into Maximilian’s service, perhaps encouraged by Dr Johannes Fuchsmagen, who had recently left a position as secretary and advisor to the politically marginalised Sigmund to enter the service of Friedrich III.[2] In May 1487, Maximilian rewarded Waldauf for his service to Sigmund and himself by appointing him to a position in the salt-works (Pfannhaus) at Hall. (The attendant administrative tasks were carried out by a proxy.)

In early 1488, Maximilian was imprisoned by the city council of Bruges. Waldauf participated in the expedition to rescue him, and in the ensuing struggles against the rebellious Flemish cities. In July 1488, Maximilian ennobled Waldauf in thanks for his efforts in “destroying the disorderly government by risking his bodily safety and his life,” and bestowed upon him the title “von Waldenstein” after a castle in Württemberg.[3]

On 6 January 1489, Maximilian and his entourage, including Waldauf, were traveling by boat from Amsterdam to “Sperdam” (Spaarndam, near Haarlem), when their boat, enshrouded by mist, hit drift ice and began to sink. While Maximilian ordered the holes to be plugged with clothing, Waldauf prayed for delivery, promising that he would establish a votive foundation if they reached their destination safely. In fulfilment of this vow, Waldauf established his foundation at Hall in Tirol, about ten kilometres east of Innsbruck.

In early 1490, Archduke Sigmund abdicated his territories to Maximilian. In the process of negotiation and transfer, Waldauf acted as intermediary between Maximilian and Sigmund, who rewarded him in 1491 with a suit of armour. Waldauf also participated in Maximilian’s campaigns in Hungary. On 17 November 1490, during the conquest of Székesfehérvár (Stuhlweißenburg), Maximilian knighted Waldauf for his bravery and appointed him as protonotary. (More troublingly, Maximilian also granted Waldauf possession of a synagogue in Stuhlweißenburg and the property of Jews living there.) Waldauf accompanied Maximilian to the imperial diets at Nuremberg (1491), Koblenz (1492) and Worms (1495), and on military campaign against France (1492/1493). He also acted as emissary to Saxony, Cologne and Hungary, where he discussed potential marriage plans and a defensive league against the Turks. His successful embassy resulted in his elevation to the Order of the Golden Spur. He was also responsible for negotiating the Spanish-Habsburg double marriage of Philip the Fair and Juana of Spain at Mechelen in 1495.

Like Maximilian, Waldauf was excited by the possibilities offered by the printing press. Waldauf was involved in the publication of the Missale Brixinense (» Augsburg: Erhard Ratdolt, 1493 [GW M24292]), and at least one of the editions of the territorial ordinance for the Tyrol (» Augsburg: [Erhard Oeglin and Hans Pirlin], 1506 [VD16 1354]).[4] He was a member of the order of Bridget of Sweden, and financed the publication of several editions of her prophecies: two Latin editions (» Nuremberg: Koberger, 1500 [GW 4392]; » Nuremberg: Peypus, 1517 [VD16 B 5594]); a German translation containing a woodcut that resembles the image of Bridget on the altar panel in Hall (» VD16 B 5596 / 5593); an abbreviated version of the German translation (» VD16 B 5595); and a broadsheet (now lost) containing fifteen prayers of St Bridget, which were to be prayed daily by the junior chaplain of the Waldauf foundation. Waldauf also wrote the text for a catalogue and description of his foundation, the Haller Heiltumbuch (A-HALn o. Sign.), which was illustrated with woodcuts by Hans Burgkmair the Elder. The Hall Heiltumbuch was probably inspired by the descriptive collection of the collection of relics at Nuremberg, printed by Peter Vischer in 1487.[5] Although the text and woodcuts for the Hall Heiltumbuch were complete and ready to go to press, Waldauf died before it could be printed. However, the autograph manuscript (with the woodcuts stuck in at the appropriate points) is still preserved in the parish archive in Hall. The volume now has 186 leaves, though a further four at the end have been lost.[6] The Heiltumbuch also refers to an earlier, smaller catalogue of the foundation’s relics, sold at the market at Hall, but no copy of this work is known to have survived.

In 1496, Maximilian appointed Waldauf as one of four counsellors to the imperial treasury (Schatzkammer, renamed Raitkammer in 1499) in Innsbruck, at the astounding salary of 461 Gulden a year. Waldauf thus played an important role in one of Maximilian’s reforms: the transformation of the Hofkammer at Innsbruck into the central accounting facility for Austria. Even if this new arrangement failed in 1500, to be replaced by the Nuremberg Regiment, Waldauf’s appointment to this office signals Maximilian’s esteem for his counsellor, and also accounts for the financial resources behind the foundation. In 1500 he was entrusted with oversight of Maximilian’s armoury, and in 1506 of all salt-works in Austria. A final sign of Maximilian’s confidence in Waldauf was his appointment as superintendent over the preparations for his grandiose funeral monument on 8 December 1509. However, Waldauf died on 13 January 1510, before the Heiltumbuch could be printed, nine years before Maximilian’s death, and decades before the emperor’s ostentatious cenotaph could be completed.[7]

The foundation

In 1492, Waldauf began formalising the foundation he had promised on the sinking boat. He developed the concept for the foundation in consultation with Maximilian, his confessor and several theologians. As Maximilian’s entourage travelled around Europe, Waldauf collected thousands of relics which would in time become one of the most impressive collections in Europe. Waldauf supplicated the pope to convince custodians of large collections of relics to donate some to support his pious purpose. Accordingly, in a brief issued on 14 March 1493, Alexander VI commanded archbishop Hermann IV of Cologne to transfer some relics to Waldauf, to encourage the faithful to visit his planned chapel more eagerly. (To carry out this mission, Waldauf would visit Cologne for two months in 1495.) On 10 July 1493, the abbot of Wilhering gave Waldauf – accompanied by Nicolas Mayoul, the head of Maximilian’s chapel (“Seiner künigklicher genaden Obristen Caplan”) – a fragment of the true cross.

This fragment, the most prestigious relic in Waldauf’s collection, may have served a particular purpose. Throughout the Kingdom of France there were several collegiate foundations called Saintes chapelles, of which that in Paris was only the most famous. By definition, a Sainte chapelle was a foundation established by a member of the (extended) royal family, containing a relic of the Passion. In many cases this consisted in a piece broken from the crown of thorns, the prize relic at the Sainte chapelle in Paris. In the Heiltumbuch (Ms., Haller Heiltumbuch, Pfarrarchv, Hall i.T., » ) the foundation’s home is often described as a heilige Capelle. If the epithet heilig here has a specific meaning rather than a general one, it is possible that the chapel in Hall – to which Maximilian stood as a second founder beside Waldauf – was intended as a Habsburg equivalent to a French Sainte chapelle.

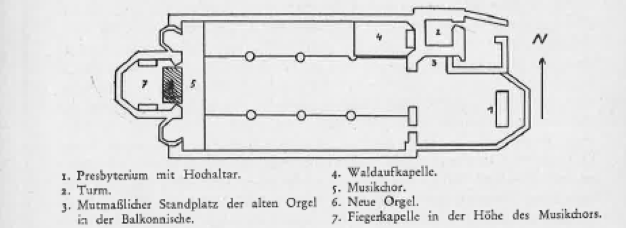

Although Waldauf’s relics were initially housed in his castle of Neu-Rettenberg (completed in about 1494), he soon realised that the collection, intended to bring spiritual benefits to the public, required a more public setting. Waldauf decided not to build the chapel for his foundation at Innsbruck, where it might be seen as competing with Maximilian’s building projects, but rather in the commercially important city of Hall, location of a significant salt-works and the imperial mint, as well as a stop on the transalpine way across the Brenner pass. The parish church of St Nicholas in Hall was already home to an important liturgical foundation and chapel, established by Hans Fieger the Elder, a citizen of Hall who had made a fortune from silver mining at nearby Schwaz. (Vgl. » Abb. Plan von St. Nikolaus, Hall in Tirol.)

Construction of Waldauf’s chapel in the church began in 1493. It is divided from the rest of the building by a splendid wrought-iron grate bearing the heraldic arms of Waldauf and his wife Barbara Mitterhofer, whom he married in 1491 (» Abb. Kapellgitter Waldaufkapelle Hall i.T.).

Waldauf paid for charters from bishops, cardinals and popes that would guarantee indulgences to those who duly performed their devotions in this chapel, even if Hall were placed under interdict. For the family crypt beneath the chapel, Waldauf procured indulgences equivalent to those of the Campo Santo in Rome. (To be sure of the efficacy of this blessing, Waldauf even had the floor of the crypt sprinkled with earth brought specially from the Campo.) In the central shrine of the altar was a statuary group representing the Coronation of the Virgin. Donor panels to the side – attributed to Marx Reichlich and now housed in the city museum at Hall – depicted Waldauf and his wife Barbara. Waldauf is presented by SS Florian and George, and his wife by St Barbara and Bridget of Sweden. The chapel was also richly decorated with silver and gold plate, and precious carpets.

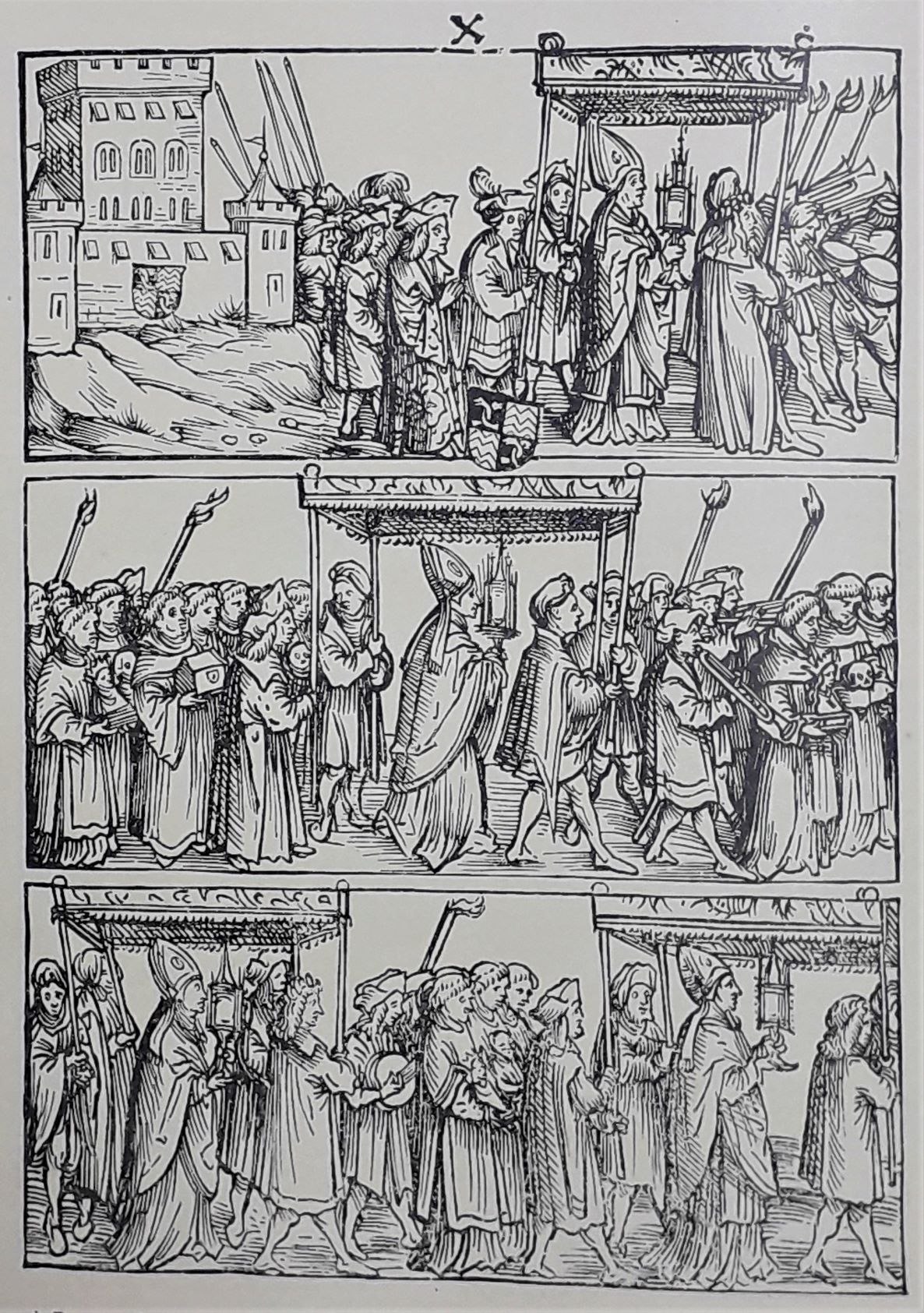

The foundation was inaugurated on 14 February 1496, but work did not stop there. Its endowment and structure were refined in further documentation, culminating in the great letter of foundation dated 29 December 1501.[8] Many of these documents emphasise Barbara Mitterhofer’s role in supporting the endeavour. Others indicate that the foundation was supported actively by Maximilian and his wife Bianca Maria, and by Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain. By 19 January 1501, construction of the chapel was sufficiently well advanced that the altar could be officially dedicated, and some of the relics brought from Neu-Rettenberg. On 9 May 1501, the relics were displayed in procession. According to the account in the Heiltumbuch, an improbable (and improbably precise) total of 32,784 people witnessed this procession, though it is likely that many of those had come to Hall simply for the spring fair rather than specifically for the procession. A woodcut made by Hans Burgkmair the Elder for inclusion in the Heiltumbuch shows several musicians in the procession (vgl.» Abb. Haller Heiltumprozession): trumpeters and timpani, a group of singers performing from books and a lutenist. (Outside, the lute would have been virtually inaudible from any distance, and may simply have kept the singers in pitch.)

The Heiltumbuch notes that the singers included the schoolmasters and pupils from Hall, Innsbruck, Schwaz and other towns in the Inn valley.

The great charter of 29 December 1501 prescribes that the foundation was to employ a senior and a junior chaplain. The benefice of senior chaplain was one of the best endowed in the empire. (The salary for the chaplains and musicians was derived primarily from an endowment of 80,000 Gulden, primarily from the rents on rural properties which Waldauf purchased for this purpose, and income from the deanery in Ambras and the salt-works at Hall, which Maximilian had diverted for this purpose in 1497. The sale of letters of indulgence was an important secondary source of income.) The senior chaplain was obliged to preach three times a week during Advent, and daily during Lent. Moreover, he was obliged to say a requiem mass for the Waldauf family weekly. The chaplains’ house contained a library, where the books were chained to the wall. The chapel in the parish church in Hall was soon found to be too small, and a free-standing building was constructed in the churchyard in 1503, where it stood until destroyed by an earthquake in 1670.[9]

On the north façade of the church, Waldauf had a two-storey wooden frame (“tabernaculum”, “Heiltumstuhl”) constructed for the exposition of relics on specified feasts, usually coinciding with a major market. This construction was modelled after one in Nuremberg, which Waldauf presumably saw in use during the imperial diet in 1491. The music during such expositions was supplied by trumpeters, trombones, pipers and choirboys. Soon the number of visitors to these events increased to such an extent that a team of chaplains had to be employed to cope with the numbers of those who wished to make their confessions, a necessary precondition for receiving the indulgences offered to those who paid their devotions.

At first, the music for the masses and offices specified by the foundation was presumably provided by a group of boys from the Latin school. In 1497, Maximilian augmented the provision of an organist and the singing of polyphonic music under the direction of the Latin school master at Hall (see below). (Between 1512 and 1519, the schoolmaster at Hall was Petrus Tritonius, known for the humanistic ode settings he wrote at the encouragement of Conrad Celtis.)[10] The singers were to perform polyphonic music (in mensuris) at vespers, mass and other services, not merely on Sundays and feast days, but on weekdays as well. In particular, they were to sing the Salve regina every evening. The repeated emphasis that Maximilian’s deed gives to the performance of music in mensuris suggests that the singing to that point may have comprised chant only. Maximilian’s foundation for the singing of the antiphon Salve regina is possibly an importation of the practice of the Salve-service, also known as Salut or Lof, popular in late mediaeval France and the Low Countries, which included not only the singing of the Salve regina, but also other music, including psalms and organ music, often in alternation with the chorus. Endowed Salve regina services are also known from other towns in the Austrian region, for example at Bozen (1400) and at St. Stephen’s, Vienna.[11]

The names of the organists who played for the foundation’s services are not known. (Unfortunately, the earliest surviving account books from the foundation date from 1733.) In 1499, Paul Hofhaimer received a payment from the city council of Hall, but it comprised only four pounds of fish and four measures of wine, which suggests a one-off appearance rather than a regular arrangement (Stadtarchiv Hall in Tirol, A-HALs, Raitbuch 8, f. 587r). It is possible that this appearance was not even in the context of Waldauf’s foundation; the record does not specify why he was paid. Nevertheless, given Maximilian’s involvement in the foundation, it is not unlikely that Hofhaimer had some involvement in the project. It is even possible that Hofhaimer’s surviving organ versets for the antiphons Salve regina and Recordare virgo mater – transmitted in the tablature books of Fridolin Sicher (» CH-SGs Cod. 530, copied 1525) and Leonhard Kleber (» D-Mbs Mus. ms 40026, copied 1520–1524) respectively – were written to permit a student unskilled in improvisation to supply the music required by the statutes of the foundation.[12] Hofhaimer was famous for his skill in improvisation, and there is no obvious reason why he would need to write down such settings except for the benefit of others.

Maximilian’s support for Waldauf’s foundation has been mentioned several times. Some of the documents of foundation also note the involvement of his wife Bianca Maria Sforza. His son Philip the Fair also visited St Nicholas in Hall on 15 September 1503, and his chapel sang in the church. This visit is commemorated by a woodcut in the Heiltumbuch: vgl. » Abb. Maximilian I., Philipp der Schöne und Florian Waldauf in Hall.

Ten days later, Philip issued a document confirming the foundation. This ratification of the rights of the foundation reinforced the close bond between the Waldauf chapel and the Habsburgs.

The documentation of the Waldauf foundation

Most of the documentation relating to the foundation is divided between the parish archive in Hall in Tirol, the city archive of Hall in Tirol (on permanent loan to the city museum), and the Reichsregisterbücher in the Haus- Hof- und Staatsarchiv in Vienna. Sixty-five documents are preserved in Hall from before Waldauf’s death on 13 January 1510. Unfortunately the library has been largely dispersed, some of it quite recently. The charters relating to the foundation provide substantial information about the music to be sung during its services. Out of the dozens of extant documents we shall discuss only some of those that mention music, or relate to the liturgy. Unfortunately, no known written musical sources can be associated with the foundation, apart from the chants included in the Heiltumbuch.

On 4 July 1496, the papal legate Leonello Chierigati issued a charter that confirmed an indulgence of forty days to those who participated in the liturgical life of the foundation. In order to take advantage of this offer, believers were to attend the mass, vespers, vigils of the dead, matins, Salve-service, sermon or other services on certain feast days during the year. Moreover, they were to pray several Our Fathers and Hail Marys in the chapel and contribute to the building, maintenance and adornment of the foundation.[13] Further indulgences were later supplied by Pope Alexander VI and several bishops.

On 4 April 1497, Maximilian contributed further to the foundation, for the sake of his soul and that of his wife Bianca Maria. He diverted some twelve Marks from the income of the collegiate church in Ambras to pay for an oil lamp to burn perpetually in the chapel, and for a Salve regina to be sung there daily.[14]

On 6 December 1497, Maximilian made a further donation to expand the musical adornment of the foundation, diverting money from the salt-works at Hall to pay for an exceptional organist (“ein berumbter geschikhter Organist”), the schoolmaster at Hall, a teaching assistant (“Jungmeister”), the acolytes and the choirboys.[15] On the same day, Maximilian issued a further charter that specified the details of this donation: each day during the mass and the Salve-service every evening, the singers were to perform polyphony (in mensuris), accompanied by the organist. These provisions were ratified in a documentary confirmation (Vidimus) issued by Leonhard, abbot of Wilten.[16]

On 19 January 1500, Konrad, suffragan to the bishop of Brixen, dedicated the altar in the Waldauf chapel. The associated documentation again specifies the daily provision of a mass and Salve, as well as the institution of the office of preacher, and specifies the days on which an indulgence was to be offered.[17]

On 29 December 1501, Florian Waldauf and his wife Barbara issued the great letter of foundation, which survives in two copies. Those in the city archives of Innsbruck (Stadtarchiv, Urk. 587) and Hall (Stadtarchiv, Urk. 304) were written on large sheets of vellum in a perfectly controlled scribal hand by the master calligrapher Hans Ried. The bifolia are held together by silk ropes and weighed down by multiple wax seals proclaiming the authority and authenticity of the documents. The production of these documents alone must have cost a small fortune. These charters summarise everything that had gone before, including the use of bells, polyphony and organ, specifying the details of their deployment on specific feasts.

A bull issued by Pope Julius II on 19 January 1507 expands the liturgical observances of the foundation even further. In addition to the previously specified services, an office of the dead was to be celebrated every Monday in the Waldauf chapel. After compline, the Salve regina and further antiphons and hymns in praise of the Blessed Virgin were to be sung.[18]

Another bull issued on 18 December 1508 specified that during the exposition of the relics during the market, three special solemn masses were to be sung (in the church, in the new free-standing chapel, and on the relic platform). Moreover, the exposition itself was to be accompanied by the singing of hymns.[19]

The liturgical music of the Waldauf foundation

The legal and procedural basis of the foundation is summarised in the Heiltumbuch. The liturgical prescriptions there include some information about the musical aspects of the liturgy:

Wie das lobgesang Salue Regina alle abent gesungen wirdet.

Zum VIII., das zu lob und eere der hochgelobten junkfrauen Marien alle abent, suntags, feirtags und werchtags, das ganz jar das lobgesang Salue Regina zu rechter gewondlicher Saluezeit, das ist nach completzeit, und nach jedem Salue alweg ain sequenz oder antifon von Vnser Lieben Frawen in mensuris und organis mit aller solempnitet in der heiligen Capellen loblichen gesungen wirden, darzu der caplan der heiligen Capellen alle abent das ganz jar ein gewondliche collecten von Vnser Lieben Frawen liset und den segen in der heiligen Capellen gibt. Und darnach gibt er auch alle abent nach dem Salue vor der heiligen Capellen den umbstenden cristenmenschen den weichprunn, zu erlangen die gnaden und aplass, so darzu verlihen sind

(Heiltumbuch, Hall in Tirol, Pfarrarchiv (A-HALn, o.Sign.), f. 37r–v, ed. Garber 1915, lxxxii).(How the antiphon Salve regina is sung each evening.

VIII. Each evening, whether Sunday, feast-day or weekday throughout the whole year, the antiphon Salve regina is sung to the praise and honour of the most Blessed Virgin Mary, at the usual time for singing the Salve, that is, after compline. After each Salve, a sequence or antiphon of Our Lady is always to be sung with all solemnity and dignity in polyphony and organ in the holy chapel. Furthermore, each evening throughout the entire year the chaplain of the holy chapel reads a usual collect of Our Lady and gives the blessing. And every evening after the Salve, he sprinkles all the faithful standing before the chapel with holy water, to bring about the associated blessing and indulgence.)Beside the Salve regina, another Marian antiphon, Recordare virgo mater, was also to be sung in the chapel:

Wie die antiphon Recordare virgo mater und Da pacem domine ze singen gestift sind.

Zum VIIII., das alle tag, suntags, feirtags und werchtags, das ganz jar ausserhalb der freitag nach einem jeden hochambt in sand Niclasen pharrkirchen zu Hall die antipfon von Vnser Lieben Frawen Recordare virgo mater, aber alle freitag die antiphon Da pacem domine knient gesungen und ain collecten darauf gelesen wirdet.

(Heiltumbuch, Hall in Tirol, Pfarrarchiv, f. 37v, ed. Garber 1915, lxxxiii–lxxxiv).(How the antiphons Recordare virgo mater and Da pacem domine are founded.

VIII. Every day throughout the year, whether Sunday, feast-day or work-day (but excluding Fridays), after each high mass in St Nicholas’ parish church in Hall, the antiphon of our Lady, Recordare virgo mater, is to be sung; every Friday, the antiphon Da pacem domine is to be sung kneeling, and then a collect to be read.)On Fridays further Marian devotions were offered:

Wie alle freitag ain respons von Vnser Lieben Frawen und die antiphon Gaude dei genitrix virgo immaculata ze singen gestift sind.

Zum X., das der pharrer und die siben gesellen und darzu all caplän und priesterschaft im pharrhof zu Hall im Yntal mitsambt dem schuelmaister alle freitag das ganz jar nach dem Benedicamus der letzsten vesper in der heiligen Capellen loblichen singen ein respons von Vnser Lieben Frawen und darzu die antiphon Gaude dei genitrix virgo immaculata, darauf dann der heiligen Capellen wochner aus dem pharrhof, der alle tag in seiner wochen die funfzehen ermanungen und gepete von dem heiligen leiden Christi, als hernach geschrieben stet, petet, ain gewondliche collecten liset und darauf den segen in der heiligen Capellen gibt. Aber am heiligen Karfreitag petet jeder priester aus dem pharrhof zu Hall zu gewondlicher vesperzeit kniende in der heiligen Capellen fünf Pater noster, fünf Aue Maria und ain glauben zu lob, eere und dank den heiligen fünf wunden und dem heiligen pittern leiden und marter unsers herrn Jhesu Christi.

(Heiltumbuch, Hall in Tirol, Pfarrarchiv, f. 37v, ed. Garber 1915, lxxxiv).(How on Friday a responsory of Our Lady and the antiphon Gaude dei genitrix virgo immaculata are to be sung:

X. Following the Benedicamus at vespers every Friday throughout the year, the parish priest, the seven associates, all the chaplains and priests in the presbytery at Hall in Tirol and the schoolmaster solemnly sing a responsory of Our Lady in the holy chapel, and then the antiphon Gaude dei genitrix virgo immaculata. Each day while he is on weekly duty, the assigned priest from the presbytery should then pray the fifteen reproaches and prayers of the holy passion of Christ, as set out below; then he should read the usual collect and then give the blessing in the holy chapel. But on Good Friday, at the normal time for vespers, every priest from the presbytery at Hall should kneel and pray five Our Fathers, five Hail Marys and a Creed in praise and honour of, and in thanks for the holy five wounds and the holy bitter suffering and death of our Lord Jesus Christ.)The Heiltumbuch also hints at the size of the musical forces required by the foundation for various services:

Zum Vierden haben sy gestift, das der caplan der heiligen Capellen alle montag, feirtags und werchtags, das ganz jar in der heiligen Capellen mit vier schuelern singet ein seligs andechtigs seelambt.

(Heiltumbuch, Hall in Tirol, Pfarrarchiv, f. 34v, ed. Garber 1915, lxxxii).Fourthly, the founders have specified that every Monday in the year, whether it is a feast-day or a work-day, the chaplain of the holy chapel and four pupils should sing a mass for the dead with devotion.

The musical forces required at the processions and expositions of the sacrament were somewhat more extensive; the Heiltumbuch mentions “cantores and choir singers” (cantorn und chorsingern), which may hint at a division between singers of polyphony and chant. These singers also sang in alternation with instruments. After the wind players performed from the relic platform, the singers sang a processional responsory in alternation with a small organ that was perhaps mounted on a cart:

Darauf plasen und hofiern auf dem heilthumbstuel zu lob und eere dem hochwirdigen heilthumb und den pebstlichen grossen Römischen gnaden und aplas die thrumetter und darnach die pfeifer und pusauner. Darnach singen die cantores zum ersten umbgang die respons Regnum mundi und der Organist slagt den vers auf ainem positiff.

(Heiltumbuch, Hall in Tirol, Pfarrarchiv, f. 124v–125r, ed. Garber 1915, cxxxii).After this the trumpeters, and then the pipers and sackbut players blow and play on the relic platform in praise and honour of the blessed relics and the great grace and indulgence of the pope of Rome. After that the singers sing the responsory Regnum mundi during the first procession, and the organist plays the verse on a positive organ.

The procession of the relics included twenty-one stations, at which a different set of relics was displayed, culminating in the fragment of the True Cross. At each station, the Heiltumbuch specifies that the choir was to sing the following responsory or antiphon:

- Regnum mundi*

- Surge virgo et nostras sponso preces aperi

- Quadam die Olybrius molestus deo et hominibus

- Pulchra facie sed pulchrior fide beata es Walpurgis

- Ipsi sum desponsata, cui angeli serviunt

- Virgo gloriosa semper evangelium Christi gerebat in pectore

- Induit me dominus vestimento salutis

- Simile est regnum celorum

- Beati estis sancti dei omnes

- Sint lumbi vestri praecincti*

- Gloriosus apparuisti inter principes Austrie, sancte Leopolde

- Isti sunt sancti*

- Absterget deus omnem lacrimam*

- Gaudent in caelis anime sanctorum

- Istorum est enim regnum caelorum

- Triumphant martyres

- Quam preciosa mors sanctorum

- Fuerunt sine querela ante dominum*

- Felix namque es sacra virgo Maria*, or Regina celi letare, alleluja

- In monte Oliveti oravit ad patrem*

- [O] Crux benedicta, quae sola fuisti digna

Some of the same chants (marked above with an asterisk) were also sung at the exposition of relics at Vienna, as described in the book In Disem Puechlein ist Verzaichent das Hochwirdig Heyligtumb so man jn der Loblichen stat Wienn jn Osterreich alle iar an sontag nach dem Ostertag zezaigen pfligt (Vienna: Winterburger, 1502 [VD16 H 3283]).[20] Other somewhat unusual chants have concordances concentrated in other Austrian sources, such as Quadam die Olybrius.

At some of the stations at Hall, the responsories and antiphons were to be preceded by the playing of trumpets, then of pipers and sackbuts (e.g. “Darauf plasen und hofiern die trumetter und darnach die pfeifer und pusauner”, Heiltumbuch, f. 139r). The display of relics from St Leopold (station 11), the Habsburg house saint, whose cult had been promoted by Friedrich III and Maximilian and whose liturgy was first promulgated with his canonisation in 1487, was a visible and audible acknowledgment of the ties between Waldauf and the Habsburgs. Gloriosus apparuisti is also transmitted as the Magnificat antiphon in the earliest liturgies to St Leopold, introduced in 1487, as witnessed by Melk Hs. 937, which contains the notation for the entire Leopold office; and in two sources without notation: a late fifteenth-century breviary, Klosterneuburg Hs. 1193, and an edition printed at Passau in about 1490 (» ISTC il00178000).[21] The Heiltumbuch provides a detailed liturgy for the twenty-first station, led preferably by a high-ranking prelate if one was present, and authorised by papal indult. The Heiltumbuch provides both the text and notation (in Hufnagel notation) for the preces and responses sung in alternation by the celebrant and the choir for this final station. The procession was completed with the singing of Christ ist erstanden in German, presumably sung by the choir and laity together. If the third Sunday after St George’s day fell on Ascension or Pentecost, Christ ist erstanden was to be replaced by Kum heiliger geist herre got, for which the Heiltumbuch provides a melody in cantus fractus notation (vgl. » Rhythmischer Choralgesang: Der Cantus fractus).

The Waldauf foundation thus represents an important witness to a complex of piety, display, ambition and emulation with several parallels in the late mediaeval Holy Roman Empire, particularly the displays of relics at Nuremberg, Vienna and the All Souls’ foundation in the castle church in Wittenberg, which Frederick the Wise stocked with sacred remains with an enthusiasm that rivalled that of Waldauf. Waldauf’s plan to print an illustrated catalogue of his collection of relics has a direct parallel in the catalogues printed for Nuremberg, Vienna and Wittenberg. But more importantly, the Waldauf foundation is a superb example of the way in which members of Maximilian’s court responded to his own promotion of liturgical foundations simultaneously as an expression of personal piety and as conspicuous displays of magnificence.

[1] Moser 2000, 11.

[2] Moser 2000, 12.

[3] Moser 2000, 13.

[4] Abkürzungen: GW: Gesamtkatalog der Wiegendrucke. Stuttgart: Hiersemann, 1925 ff. http://www.gesamtkatalogderwiegendrucke.de. VD16: Verzeichnis der im deutschen Sprachbereich erschienenen Drucke des XVI. Jahrhunderts. 24 vols, Stuttgart: Anton Hiersemann, 1983–2000. www.vd16.de.

[5] Similar catalogues appeared for the Vienna collection in 1502, and the collection of the Saxon Elector Friedrich at Wittenberg in 1509, with woodcuts by Lucas Cranach the Elder; » Kap. Das Wiener Heiligtum.

[6] Ed. Garber 1915.

[7] Moser 2000, 18–40.

[8] Hall in Tirol, Stadtarchiv, Urkunde 304; digest in Moser 2000, 96–102.

[9] Moser 2000, 32.

[10] Further on Tritonius, see » Kap. Humanists and musicians.

[11] See » Kap. Das Salve regina des Rats; » Kap. Musikalische Stiftungen bis ca. 1420. There is every possibility that such ceremonies included polyphonic singing from the early part of the century.

[13] Hall in Tirol, Stadtarchiv, Waldaufstiftung Urkunde 29, digest in Moser 2000, 75–76.

[14] Hall in Tirol, Stadtarchiv, Urkunde 273, digest in Moser 2000, 78.

[15] Hall in Tirol, Pfarrarchiv, Urkunde 437; later copy in Hall in Tirol, Stadtarchiv, Urkunde 274; digest in Moser 2000, 80–81.

[16] Hall in Tirol, Stadtarchiv, Waldaufstiftung Urkunde 34; digest in Moser 2000, 81.

[17] Hall in Tirol, Stadtarchiv, Waldaufstiftung Urkunde 44; digest in Moser 2000, 90.

[18] Hall in Tirol, Pfarrarchiv, Urkunde 437; digest in Moser 2000, 112–114.

[19] Hall in Tirol, Pfarrarchiv, Urkunde 484a; digest in Moser 2000, 118–121.

[21] Incunabula short-title catalogue (The British Library, https://data.cerl.org/istc/_search). See Rudolf 1957; Merlin 2012.

Empfohlene Zitierweise:

Grantley McDonald : „The Waldauf foundation at St Nicholas’ church, Hall in Tirol“, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/essays/waldauf-foundation-st-nicholas-church-hall-tirol> (2019).