Dance, Society and Politics

Of the several treatises mentioned above, those by dance masters of Italian courts are particularly illuminating in their justification of the place of dance in elite society. Written by maestri di ballo such as Domenico da Piacenza and his students Antonio Cornazano and Guglielmo Ebreo da Pesaro, these texts convey the importance of dance for learning correct deportment and movement both within dance and in day-to-day interactions, as embodied in the slow, graceful steps of the bassa danza. These dance manuals outline the best qualities of a courtly dancer – male and female - which included the ability to remember the dance steps, to keep time, and to perform in a slow undulating motion with care and grace. Knowledge of these movements was essential to one’s belonging to the right social class and distinguished the elite from the lower classes whose vulgar movements, as Jennifer Nevile describes, ‘exposed to others the baser nature of their souls’.[17] Yet the dance treatises also sought to present these practices on an intellectual level: due to the restraint, order and precision required of dance, it was suggested that these practices had earned a place within the humanist education that was expected of all those in power, who were themselves to be restrained by virtuous aims for the common good.[18]

In addition to the qualities of deportment and self-control that courtly dances were designed to promote, they also communicated particular social hierarchies and groupings, often to the exclusion of others. The first dance of a gathering was usually described in the most detail in contemporary accounts (as demonstrated by those from Worms and Mechelen, above). This was led by the participant of highest social standing, who was frequently identified by name (as was their dance partner) in reports, with features of their dress – another marker of elite status – also being recounted in some detail. Who danced with whom was significant: the partner of the dancer of highest status was also regarded as being of social or political importance, at least in that particular setting.

This strict social hierarchy of dance pairings in Germany was described in detail by Antoine de Lalaing, a courtier of Maximilian’s son Philip, during a visit of the latter to Ulm in 1503. There de LaLaing observed a dance in which Philip, as the gentleman of highest rank, danced with the lady of highest status, subsequent pairings being made likewise, in decreasing order of rank. De Lalaing further noted that if the King danced, he would be surrounded by four dukes, carrying torches if at night, other nobleman being accompanied in a similar fashion by those next in rank.[19] This practice can also be traced in other German cities. In Worms in 1494, as noted earlier, the Count Palatine danced with the Queen, surrounded by eight counts who held torches. In Cologne on 23 June 1505, Maximilian performed the first dance with the Duchess of Lüneburg, four counts carrying torches in front of him and several other princes dancing behind.[20] Further examples of socially significant dance pairings are found in other reports from Maximilian’s and Philip’s travels through the Habsburg territories. In Innsbruck in 1502, for example, de Lalaing recounted how Maximilian led a dance ‘in the German style’ with one of the Queen’s ladies-in-waiting, while Philip himself danced with Bianca Maria (» I. Kap. Jousts and dances for Philip). Furthermore, as described above, during the wedding celebrations in which Maximilian and Bianca Maria participated in Mechelen in 1494, the bride that day was honoured by a dance with Elector Friedrich of Saxony.

Dances were not only shaped by social customs, but also reflected – and enabled – important political interactions. In January 1502, for example, the Venetian ambassador Zaccaria Contarini reported home from Innsbruck of a dance at the royal court from which he had been excluded as a result of political tensions between Maximilian and the Signoria of Venice. Bianca Maria had apparently remarked to the King that, if Contarini were not invited to the dance, she would not attend either.[21] The presence of the ladies of a court, and not only the Queen, was integral to the success of a dance and the political interactions that consequently arose.[22] Women’s conduct and their contact with royal or noble peers was important, not only because their appearance and behaviour reflected on their families, but also due to the possible diplomatic conversations that dances afforded. In February 1504, for example, another Venetian envoy, Francesco Capello, reported that he had spoken to Queen Bianca Maria during a dance about the fact that the current King of Portugal was still without an heir.[23]

The importance of dance to Maximilian, in the social correctness that it conveyed and the political interactions that it enabled, is not only documented in contemporary accounts of court life, as exemplified above. It is also communicated through the literary works that Maximilian himself commissioned to represent the cultural significance of his reign in an embellished, pictorial form. Freydal, for example, prepared in c.1512-1515, presents Maximilian as the eponymous hero of the piece and traces his quests through 64 courts to reach his first wife, Mary of Burgundy. Although never finished — only five of the planned woodcuts were completed — the surviving miniatures that were to act as sketches for the final prints of the work reflect the importance of dance for the representation of the king. At each court that Freydal visits, he participates in jousts and other forms of combat, followed by a dance, as was typical of courtly ritual of the time.[24]

While Freydal might be regarded as representing various dances, including some that might reflect practices described in the aforementioned Burgundian, French and Italian treatises (see, for example, » Abb. A round dance and » Abb. A processional dance), it nevertheless focuses on one aspect of dance that, though rarely described in these dance manuals, was obviously of great importance to Maximilian: the mummery. The contents of the Freydal manuscript confirm that all of the dances depicted were indeed ‘mummeries’, that is a coordinated dance performed in costume. It lists the names (with corrections in the king’s own hand) of all the ladies before whom, and all the gentlemen with whom Freydal is shown as having ‘gerennt, gestochen, gekämpft und gemummt’.[25] The mummeries are variously described with exclamations of wonder (‘wunderbar’, ‘ausbündig’, ‘herlich’), with details of the colour or form of the participants’ costumes (‘in gestallt der vogel’, ‘von hübschen wolriechenden bluemen aller varben, die man kan erdencken’), or an indication of the style of the dances, which range from the more traditional (‘subtil’, ‘holdselig’) to the grotesque and ridiculous (‘seltsam’, ‘frembd’, ‘abentthurig’, ‘lächerlich’, ‘wild’). The miniatures themselves reflect this variety of costumes and dances: in Freydal’s mummeries, the male participants (including the King) are masked, and all male dancers (i.e. not including the King, who is always shown overseeing each performance, holding a torch) appear in the same costume. The dances can largely be distinguished between ‘character’ dances (i.e. those representing particular nations, personalities and communities, such as huntsmen, miners, giants and women, as well as Burgundians, Hungarians, Turks and Venetians), which have more measured steps in keeping with the courtly dances described above; and those regarded as ‘grotesque’, in which the dancers’ costumes are more unusual and their dances involve more comical movements and jumps, distorting the courtly grace usually required of such pastimes.[26] The ladies depicted do not participate in the latter, nor are they usually costumed: they only appear in the typical dances of the court, in appropriate courtly dress.

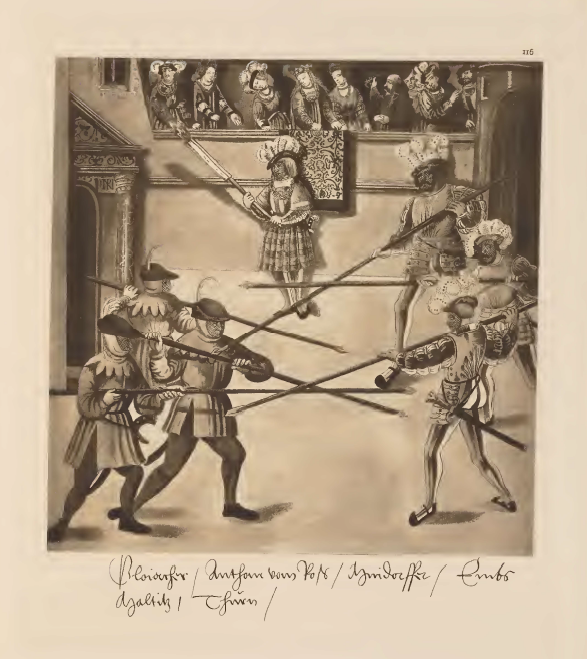

Although not named as such, several of the more theatrical mummeries depicted in Freydal appear to symbolise dances that are often described as ‘Moriskentanz’ or ‘Morisca’ in contemporary reports. These terms were often used to describe the representation of regions south of Europe in costumed dances, in which the male participants might have their faces painted or covered by a mask or netting, and wear quasi-foreign costumes, adorned with small bells. More generally, however, the ‘Moriskentanz’ was associated with portrayals of strangeness or silliness which could take a number of forms, such as dancing in a circle around a soloist; or the representation of a battle - often between the Christians and the Moors or Turks (see, for example, » Abb. Dancers dressed as soldiers). Otherwise, a ‘Morisca’ might entail a lady of the court judging the best of a group of dancers, who were usually dressed as fools and vied with each other in their grotesque movements

On the relief of the balcony of Maximilian’s Innsbruck residence, Bianca Maria, positioned between Maximilian and Mary of Burgundy, offers an apple as a reward to several such dancers, who are dressed elegantly, but with bells on their ankles and wrists (» Abb. Morisca dancers (relief)). While Freydal identifies the dancers depicted on its pages as nobility or members of the court, professional dancers were also often employed for dances that entailed displays of greater theatricality and more extreme movements not appropriate for those of courtly status. Such professional dancers might perform before or with those of the court — Castiglione advised that when noblemen were involved in such lively performances, these should not take place in public.[27]

[17] Nevile 2004, 2.

[18] Gombosi 1941, 298; Nevile 2004, 1-3.

[19] Gachard 1876, 305-306; for a German translation of the text, see Jungmann 2002, 65-66.

[20] Fucker 1505 (not paginated), quoted in Kelber 2018, 128.

[21] RI XIV,4,1 n. 15882, in: Regesta Imperii Online: http://www.regesta-imperii.de/id/1502-01-09_1_0_14_4_0_49_15882

[22] Kelber 2018, 124-7.

[23] Forthcoming in Regesta Imperii Online.

[24] Franke and Welzel 2013, 34-40.

[25] Leitner 1880-1882, IV.

[26] Leitner 1880-1882, LIII.

[27] Locke 2015, 115, 117-125; Franke and Welzel 2013; Welker 2013; Vignau-Wilberg 1999, 76.

[1] Unterholzner 2015, 51; Wiesflecker 1971, 372-9.

[2] Annotations on the diary of Reinhart Noltz, Mayor of Worms, in: Boos 1893, 379. Translations of this and the following citations by Helen Coffey, unless stated otherwise.

[3] Neudecker and Preller 1851, 231.

[4] Hegel 1874, 732.

[5] Letter from Barbara Crivelli Stampi to Anna Maria Sforza, Duchess of Ferrara, 24 January 1494. Full transcript in Aigner 2005, 76-7.

[6] Guglielmo di Ebreo claimed that anyone who had studied the exercises in his treatise (1463) would be able to master the dance of any nation. See Nevile 2008, 13.

[7] See note 5.

[8] Amongst the earliest and most significant treatises of the fifteenth century are those prepared by dance masters of the Italian courts, which include Domenico da Piacenza’s De arte saltandi e choreas ducendii (c.1440-50), Antonio Cornazano’s Libro dell’arte del danzare (first version (now lost), 1455; second version, 1465) and Guglielmo Ebreo da Pesaro’s De Pratica Seu Arte Tripudii (1463). French and Burgundian dance practices and repertoire are conveyed in the basse danse manuscript associated with the Burgundian court of Maximilian’s daughter Margaret (now Bibliothèque Royale de Belgique MS 9085, c.1470-1501) and the related printed treatise L’Art et Instruction de Bien Dancer (published in Paris by Michel Toulouze, in or before 1496). For these, and later dance treatises, see Nevile 2004 and Heartz 1958-1963.

[9] See Heartz 1958-1963 and Heartz and Rader 2001a.

[10] See Heartz 1966; Heartz and Rader 2001b.

[11] Heartz 1958-1963, 290; Nevile 2004, 21.

[12] Sparti 1986, 347; Heartz and Rader 2001a.

[13] Aigner 2005, 45-54; Nevile 2004, 26-7. See also Sparti 1986 and Brainard 2001.

[14] Gombosi 1941, 294, 299-300; Heartz 1958-1963; Strohm 1993, 348, 553.

[15] Aigner 2005, 45-54; Nevile 2004, 26-7.

[16] Heartz 1966, 19. A significant use of the melody occurred in the Missa La Spagna by Henricus Isaac: see Mücke-Wiesenfeldt 2012.

[17] Nevile 2004, 2.

[18] Gombosi 1941, 298; Nevile 2004, 1-3.

[19] Gachard 1876, 305-306; for a German translation of the text, see Jungmann 2002, 65-66.

[20] Fucker 1505 (not paginated), quoted in Kelber 2018, 128.

[21] RI XIV,4,1 n. 15882, in: Regesta Imperii Online: http://www.regesta-imperii.de/id/1502-01-09_1_0_14_4_0_49_15882

[22] Kelber 2018, 124-7.

[23] Forthcoming in Regesta Imperii Online.

[24] Franke and Welzel 2013, 34-40.

[25] Leitner 1880-1882, IV.

[26] Leitner 1880-1882, LIII.

[27] Locke 2015, 115, 117-125; Franke and Welzel 2013; Welker 2013; Vignau-Wilberg 1999, 76.

[28] ‘zu frewden seinem volk und zu eren der frembden geest … ist [er] in sonderhait geren in der mumerey gegangen’. See Schultz 1888, 82-4; also Franke and Welzel 2013, 35 and Kelber 2019, 59.

[29] ‘At in aulicorum suorum nupciis conseuit frequenter conmutatis vestibus in gencium aliquarum ritum personatus coram populo saltare. Qua humanitate atque liberalitate sibi multum fauoris tum principum tum populi precipue soeminarum conciliauit.’ See Chmel 1838, 91 for a transcript of the original text; a German translation is presented in Ilgen 1891, 57-8 and quoted in Gstrein 1987, 94.

[30] Barozzi 1880, 216.

[31] Quoted in Kelber 2018, 123-4.

[32] Letter from Mercurino Arborio di Gattinara to Maximilian’s daughter Margaret, 22 November 1507, quoted in Kooperberg 1908, 363.

[33] Heartz and Rader 2001c; Sutton et al. 2001.

[34] Translation from Guthrie and Zorzi 1986, 19.

[35] See Kelber 2019, 66-67; also Schwindt 2018, 83.

[36] Meyer 1981, 64-66, Brainard 1984, Wetzel 1990; also Brinzing 1998, 133-134.

[37] Reicke and Reimann 1940, 439-440 and 496. An English translation of Dürer’s letter is in Fry 1913, 26; Beheim’s letter is translated into French in Meyer 1981, 63.

[38] See Habich 1911, 234; also Kelber 2019, 252.

[39] Translation adapted from Young 2013, 46. Also cited in » H. Kap. Eine süddeutsche Humanistenkorrespondenz (Markus Grassl), with further explanation.

[40] See Meyer 1981, 63-64, Polk 1992, 141-2.

[41] Translation adapted from Young 2013, 47.

[42] Young 2013, 46.

[43] See Heartz 1966, 19-20 and Polk 1992, 135, 139.

[44] Heartz 1966, 20-26.

[45] Habich 1911, 220. For another pictorial document of civic dancing and musicians, see » E. Kap. Musik im Dienst, und » Abb. Patrizierfest.

[46] See Polk 1992, 141; Brinzing 1998, 139-140; Kelber 2018, 136-8. Further on the MS, see » H. Kap. Schubinger und das Augsburger Liederbuch (Markus Grassl).

[47] For an overview of the restrictions see Brunner 1987.

[48] Stiefel 1949, 135.

[49] Brunner 1987, 58-63; Salmen 2001, 165.

[50] Quoted in Polk 1992, 11.

[51] Nuremberg Staatsarchiv, Rep.60a (Ratsverlässe), Nr.259, fol. 5v.

[52] Brunner 1987, 58.

[53] Salmen 1992, 23; see also Salmen 1995.

[54] Vogeleis 1979, 228.

[55] Salmen 2001, 174.

[56] Ernst 1945, 203.

[57] Schwindt 2018, 83-4.

[58] Gstrein 1987, 81.

[59] Polk 1992, 109. See also » E. Musiker in der Stadt (Reinhard Strohm).

[60] On surviving written sources related to Stadtpfeifer and their music (Maastricht fragment and others), see also Strohm 1992; Brown and Polk 2001, 127.

[61] Polk 2003, 98-104; see also, Heartz 1958-1963, 313-316; Heartz and Rader 2001b.

[62] Polk 1992, 161.

[63] Schünemann 1938, 53.

[64] See Welker 2013, 76.

[65] ‘so ließ die künigliche majestat derselben nacht ein tantz auf dem rathaus halten und mancherlei tentz auf welsche und niderlendische art üben und spil treiben, darin auch der kunig persönlich in einem schempart was.’ in: Hegel 1874, 732.

[66] Several references in the records of Nuremberg’s council refer to permission granted for use of the Stadtpfeifer, Stadtknechte and Schützen for the butchers’ annual Shrovetide dance. See, for example, Nuremberg Staatsarchiv, Rep.60b (Ratsbücher), Nr. 4, fol. 156r (1486), fol. 228v (1487), Nr. 5, fol. 4v (1488) and Nr. 6, fol. 2r (1493). For the development of and sources for the Schembartlauf, see Sumberg 1941 and Roller 1965.

[67] ‘Der ro. kinig und sein sun Philipps sind zü pfingsten 1496 hie gewessen. da hat man 10 füder holtz auff den Fronhoff gefiert, und nach ave Maria zeit ain himelsfeur gehebt, und hertzog Philipp und sein adel haben 3 mall um das feur dantzt, und sind da all trumether gewessen, und hand da ob 10000 menschen dantzt.’ in: Roth 1894, 71-72.

[68] Quoted in Kelber 2018, 128.

[69] Donauwörth Stadtarchiv, Johann Knebel, Stadtchronik (unpublished), fo.206v (cited in correspondence from Donauwörth Stadtarchiv).

[70] Quoted in Gstrein 1987, 86.

[71] Gstrein 1987, 88.

[72] ‘sunst ist noch ein Klein peucklin, das haben die frantzosen und niderlender ser zu den Schwegeln gebraucht, und sunderlich zu dantz, oder zu den hochzyten.’ (there is also a small kettledrum, which the French and Netherlanders have often used, above all for dancing or for weddings). Quoted in Gstrein 1987, 91.

[73] Gstrein 1987, 89; Schwindt 2018, 81-2.

[74] Hoffmann-Axthelm 1983, 96. See also Green 2011, 17.

[75] Sumberg 1941, 88.

[76] Translation from Sutton 1967, 39, 47. See also Brunner 1983, 54-5.